Elbows Up in 1775

An Exodus That Repelled American Invasion

A quarter millennium ago tomorrow — on May 31st 1775 — Guy Johnson left his home on the Mohawk river in the province of New York, as he later testified, “at the head of 90 Mohocks and about 120 White men.”

Johnson had been acting superintendent of ‘Northern Indians’ and “His Majesty’s agent to his faithful subjects and allies the Six Nations” since his uncle Sir William Johnson had died on July 11th, 1774 – less than eleven months earlier. Among the Mohawks travelling with him was Thayendanegea, also known as Joseph Brant — a war chief, Indian Department officer and secretary to Johnson whose official position in 1775 was “Interpreter for the Six Nations Language.”

(Thayendanegea as portrayed during his 1775-76 visit to London by George Romney, now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada.)

Guy Johnson and Thayendanegea were fleeing to stay one step ahead of a threat of arrest, which had been relayed to them by friends in Albany and Philadelphia, where representatives to the continental and New York congresses justifiably suspected the Indian Department superintendent and his officers of turning First Nations against the rebellion. Following a practice launched by Samuel Adams in 1772, New York province had formed a committee of correspondence in May 1774. Tryon county, where the Johnsons were prominent magistrates and militia officers, had formed its own committee on August 27th, 1774. Since the battles of Lexington and Concord, which took place near Boston on April 19th, 1775, these committees of safety, correspondence and protection had been on a war footing.

In early May they sent a delegation to Sir William’s eldest son Sir John Johnson, Guy’s cousin and brother-in-law, to discourage him from arming his tenants. They issued a caution to Guy Johnson and stripped him of his military ranks.

The Johnsons and their followers remained defiant. On May 11th, the “principal Inhabitants and Freeholders of the Mohawk District in the County of Tryon,” which included many Johnson family associates, drew up an agreement to defend themselves on the grounds that “some of the New Englanders threaten this County, and also to offer Violence to some persons of Consequence & Character therein.” The document noted that these outsiders had already taken twelve British soldiers prisoner at Albany and “calling to mind the Duties incumbent on us both as Subjects and a free People” resolved to defend their persons and property from further disturbances.

For rebel leaders, the loyalists of Tryon county were an irritant, but after Lexington and Concord their military focus turned to Canada, which they saw as the root of loyalist or ‘Tory’ resistance. The first Continental Congress had invited French Canadians and Nova Scotians to send delegates — just one month after its first meeting in 1774. Congress renewed their appeal to French Canada in May 1775. In the meantime, Green Mountain boys under Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold — with a commission from the Massachusetts committee of safety — took Fort Ticonderoga on May 10th, captured Crown Point on May 11th and raided Fort St-Jean on the Richelieu river on May 18th before falling back to Ticonderoga to make further military preparations. Several indigenous chiefs and landowners from the Mohawk district had fought to defend St-Jean before returning to Guy Park in late May.

On May 22nd, New York formed its first provincial congress, with Peter Van Brugh Livingston as chairman. It initially struck a conciliatory note by putting forward a “plan of Accommodation between Great Britain and America.” But the first individual case it took up was that of Guy Johnson, with whom Livingston had a sharp exchange of letters after which Johnson refused further dealings with "leather dressers." Johnson knew this congress had him in their cross-hairs, but refused to make further concessions to such a body, which he rightly considered illegitimate.

"I should be much obliged for your promises" of safety, he wrote, "did they not appear to be made on condition of compliance with continental or provincial congresses, or even committees . . . many of whose resolves may neither consist with my conscience, duty or loyalty." On May 22nd, the Albany Committee received a message from ‘Little Abraham’, an elected Mohawk pine tree chief named Teiorhéñhsereˀ, saying:

“We hear that … Troops are coming … to apprehend and take away by violence our Superintendent and extinguish our Council Fire, for what reasons we know not. Brothers, we shall support and defend our Superintendent and not see our Council Fire extinguished. We have no … purpose of interfering in the dispute between Old England and Boston, the white People can settle their own Quarrels between themselves, we shall never meddle in those matters.”

On May 24th, the “Mayor, Aldermen and Commonalty of the city of Albany” sought to allay the concerns of Teiorhéñhsereˀ by stating they were unaware of any planned arrests and assuring him that supplies of gunpowder to Haudenosaunee allies – halted in the wake of the battles of Concord and Lexington and retaliatory actions on Lake Champlain and the Richelieu – would soon resume.

(Guy Park, a Georgian manor in Amsterdam, New York, built by Sir William Johnson in 1766 for his deputy, nephew and son-in-law Guy Johnson, who was married to Sir William’s daughter Mary, or Polly. Destroyed by lightning in 1773, Guy Park was rebuilt in 1774. After the Johnsons left, it served as a tavern and hotel and was owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution. The state of New York purchased Guy Park in 1907. It is now managed by the New York Power Authority and the NYS Canal Corporation. Guy Park housed the Walter Elwood Museum [dedicated to Mohawk valley history] for several years up to 2011, when flooding caused by Hurricane Irene forced the museum to relocate. The house has been restored but the Montgomery county website notes “future uses of the building are unclear.”)

On May 25th, Teiorhéñhsereˀ met again with rebel representatives from Albany at Guy Park, Johnson’s house on the Mohawk opposite the village of Teiontontaroka, or Fort Hunter. The Mohawk chief expressed relief at receiving reassurances “for we have but one head, and that is Colonel Johnson, our Superintendent. We heard that there were designs against him, and we must Protect him. We cannot do without him.”

Yet rumours of impending detentions continued to flow into Guy Park. In evidence given to the loyalist claims commission in 1786, Johnson cited a source in Philadelphia informing him “of a Design proposed in Congress to make your Memorialist prisoner as a necessary political Measure to facilitate the Alienation of the Indians from the interest of the Crown.” As a result, Johnson had fortified Guy Park and maintained 280 of his neighbours nearby for two weeks. He had also received “private instructions from General Gage,” the general commanding British forces in America, to leave the Mohawk and proceed to Canada.

In a memorial presented to the same commission, a Johnstown settler named Alexander Cameron — one of three leaders of a group of seventy that had arrived on the Mohawk from Glenmoriston in 1773 — recalled that “at the beginning of the late Rebellion in 1775 (he) was chosen by Colonel Guy Johnson as one of the Guard who was to defend him from the repeated assaults offer’d him by the Adherents of Congress, and faithfully executed the trust in him so reposed, at the risk of your Memorialist’s life & Property until the Colonel escaped to Fort Stanwix.”

As an explanation for the Mohawk nation’s decision to leave their district, Thayendanegea referred to the Covenant Chain, a complex system of Haudenosaunee alliances launched with the Dutch in the early seventeenth century, reconfirmed in 1665 by the English colonial authorities. As Brant put it: “We were living at the former residence of Guy Johnson, when the news arrived that war had commenced between the King’s people and the Americans. We took but little notice of this first report; but in a few days we heard that five hundred Americans were coming to seize our superintendent. Such news as this alarmed us, and we immediately consulted together as to what measures were necessary to be taken. What once reflected upon the covenant of our forefathers as allies to the King, and said, ‘It will not do for us to break it, let what will become of us.’” Lieutenant-General Haldimand, soon to take over from Carleton as governor of Canada, had also given assurances that whatever property was lost “the King will make up to you when peace returns.”

Also among the Mohawk leaders accompanying Johnson were John Deserontyon, known as Odeserundiye, a Mohawk war chief in Teiontontaroka, and almost certainly Aaron (Oseraghete) and David Hill (Karonghyontye), both chiefs of the Mohawk nation’s bear clan. For these indigenous leaders, the decision to leave was difficult, but as Deserontyon later put it, “we thought that it would be very hard if we should lose them for it was only them helped us.”

(Colonel Guy Johnson and Karonghyontye [Captain David Hill] in a portrait painted in London in 1776 by Benjamin West, now in the National Gallery of Art, London.)

As Guy Johnson departed, he was also accompanied by his deputies Daniel Claus, a German immigrant married to another daughter of Sir William Johnson, and Dr. John Dease, from family that were also close relations of the Johnsons in county Meath, as well as Indian Department secretary Joseph Chew. The party also included Indian department interpreter John Butler and his sons Thomas and Walter, as well as other key associates of the Johnson and Butler families such as Gilbert Tice, an inn- and tavern-keeper at Johnstown who also spoke multiple indigenous languages. They were joined by dozens of Highland Gaels from Glengarry, Glenmoriston, Knoydart and adjoining areas of Ross-shire, most of whom had emigrated in 1773 or 1774.

As a pretext for leaving, Johnson gave out that he was heading for German Flats on the Mohawk to convey congressional assurances to indigenous allies. Instead he proceeded further up the Mohawk to Fort Stanwix, where he met Six Nations leaders and sent express messengers to Niagara, Detroit and other posts, calling First Nations representatives to assemble at Oswego on Lake Ontario.

From June 17th to July 8th, Johnson held a large formal conference at Oswego with 1,456 representatives of the Haudenosaunee and the other indigenous leaders from the Great Lakes watershed and the Ohio valley. They agreed to defend lines of communication in the St. Lawrence valley and the Great Lakes from American attack, but decided against taking the fight into the rebellious colonies themselves — a decision which the Haudenosaunee would only briefly reverse in 1777.

Now that Johnson was safely clear of congressional reach, he adopted a less confrontational tone. In a July 8th letter to Livingston, Johnson said: “I trust I shall always manifest more humanity than to promote the destruction of the innocent inhabitants of a Colony to which I have been always warmly attached — a declaration that must appear perfectly suitable to the character of a man of honour and principle who can on no account neglect those duties that are consistent therewith however they may differ from sentiments now adopted in so many parts of America.”

In the meantime, the new American committees of safety and congresses were doing the opposite. On June 6th, the Albany committee advised freeholders of Albany and Tryon counties to nominate candidates for New York’s first state election. On the same day, the New York congress recommended Philip Schuyler to be a major general in the colonial army. On June 14th, 1775 the second continental congress authorized the formation of the continental army. On June 27th, it authorized an invasion of Canada to be commanded by Schuyler.

While Johnson was still at Oswego, tragedy befell his family: on July 11th, his wife Polly Johnson died in childbirth; Johnson was left with two young daughters. By mid-July he and his party were at Akwesasne, an indigenous settlement on the St. Lawrence alongside a Roman Catholic mission known as St. Régis. By July 17th they had arrived at Kahnawake, the major indigenous centre opposite Lachine, where he held a large conference with the First Nations of Canada.

On the same day the continental army was formed — June 14th 1775 — Guy Carleton issued commissions for officers in the Royal Highland Regiment, later numbered the 84th regiment of foot. At least four Highlanders named McDonell from the party led by Johnson and Brant joined as officers and three dozen more – nearly half named McDonell – joined as privates.

(Sir Allan Maclean of Torloisk, 1725-98)

The commander of the first battalion of this new regiment, a former Jacobite veteran of the battle of Culloden and British officer in the Seven Years War, was Allan Maclean of Torloisk on the isle of Mull, who strongly advocated military plans to recapture New York. In a letter to Guy Johnson dated July 8th, 1775, Maclean wrote: “it will be necessary to clear the road and make it straight to the Fireplace.” By this he meant an expedition to re-take Johnson Hall, Canajoharie and Teiontontaroka/Guy Park/Fort Hunter on the Mohawk by opening two corridors to Albany — one southward from Montréal along the Richelieu/Hudson and a second one eastward from Oswego along the Mohawk downriver from Fort Stanwix.

Brant, Butler and John McDonell, a new ensign in the 84th, also favoured this forward policy, while Carleton and most First Nations opposed it. After 1777 Butler, Brant, McDonell and Tice became officers in the Indian Department and a new regiment named Butler’s Rangers; they brought the war to the Mohawk valley and other parts of New York province with raids and ambushes over the next five years.

In the meantime, the Americans had launched a full invasion of Canada. In September 1775, they made three major attempts — each repulsed — to take the lightly-defended Fort St-Jean. Once the new, Irish-born US general Richard Montgomery had received reinforcements that boosted his continental army force to 1,700, St-Jean’s fate was sealed. John Deserontyon, sent to Johnson Hall from Montreal with letters for Sir John Johnson, arrived back at St-Jean in time to re-join its defence but only narrowly escaped capture when it fell on November 3rd.

On September 25th Ethan Allen was captured near Montréal in an action where Peter Warren Johnson — a subaltern in the 26th regiment of foot and the eldest son of Sir William and Molly Brant, Joseph’s sister — distinguished himself. Once American reinforcements arrived, Montreal fell to the continental army on November 13th. Carleton was nearly seized near Sorel, where ensign McDonell was captured.

The next challenge was the defence of Québec, now vulnerable due to the untimely transfer of a number of British regiments to Boston in late 1774. Upon learning that St-Jean would fall, Maclean redirected his contingent of about two hundred 84th regiment soldiers to the capital, where he arrived on November 12th. Carleton arrived a week later. When over six hundred American soldiers assaulted the fortress of Québec on New Year’s Eve – December 31st, 1775 – the defenders were few.

Maclean commanded just over two hundred Royal Highland Emigrants under fourteen officers, as well as about one hundred British regulars, mostly Royal Fusiliers, but including marines, artillerymen and soldiers from the 26th. They were backed by up to one thousand non-professional soldiers: five hundred militia, mostly French Canadian, four hundred sailors and eighty artificers, carpenters and engineers.

Most reports of the battle credit Maclean and his officers with cool-headed leadership at crucial moments that prevented a breakthrough and ultimately defeated the American attack. In a report to London, Carleton described the battle as follows:

“Two real attacks took place upon the Lower Town: one under Cape Diamond, led by Mr. Montgomery, the other by Mr. Arnold, upon the part called the Sault au Matelôt.

This at first met with some success, but in the end was stopped.

A sally from the Upper Town under captain LAWS attacked their rear, and sent in many prisoners, captain M’DOUGAL afterwards reinforced this party, and followed the rebels into the post they had taken.

Thus Mr. Arnold’s corps, himself and a few others excepted, who were wounded and carried off early, were completely ruined. They were caught as it were in a trap; we brought in their five mortars and one cannon.

The other attack was soon repulsed with slaughter. Mr. Montgomery was left among the dead.

The rebels have on this assault between six and seven hundred men, and between forty and fifty officers, killed, wounded, and taken prisoners.

We had only one lieutenant of the Navy doing duty as a captain in the garrison, and four rank and file killed, and thirteen rank and file wounded, two of the latter are since dead.”

Captains George McDougall and George Laws were from the 84th whose other officers included John Nairn, who saved Laws’ life at a pivotal moment, and Malcolm Fraser, who sounded the alarm when the New Year’s eve attack was detected.

Guy Johnson, Brant, Claus, Chew, Tice and David Hill missed this engagement, as they had travelled to London in November to contest Carleton’s reorganization of the Indian Department. John Butler and John Dease had been sent to Niagara in late 1775. John Deserontyon returned to the Mohawk in early 1776.

The successful defence of Québec was followed by another victory along one of the two corridors to Albany that discouraged further American invasions. Brant, Deserontyon, Butler and John McDonell all played crucial roles in the battle of Oriskany near Fort Stanwix on August 6th, 1777. But this indigenous and Canadian military success was followed by a tactical withdrawal instead of a concerted push into the Mohawk valley. Later in 1777, the catastrophic failure of the Burgoyne expedition — a much larger offensive along the second corridor southward from Montréal, where indigenous and loyalists units were less involved — put an end to any remaining illusions that America could be re-conquered from Canada.

In the years that followed, Butler’s Rangers, the King’s Royal Regiment of New York (founded by Sir John Johnson in Canada in 1776) and parties of indigenous warriors continued to raid New York to deter American offensives, while the 84th garrisoned posts along the St. Lawrence and on the Great Lakes.

As the US prepares to celebrate the 250th anniversary of its army and its president revives talk of making Canada the 51st state, we do well to recall the first American invasion of Canada, which shaped our country in profound ways.

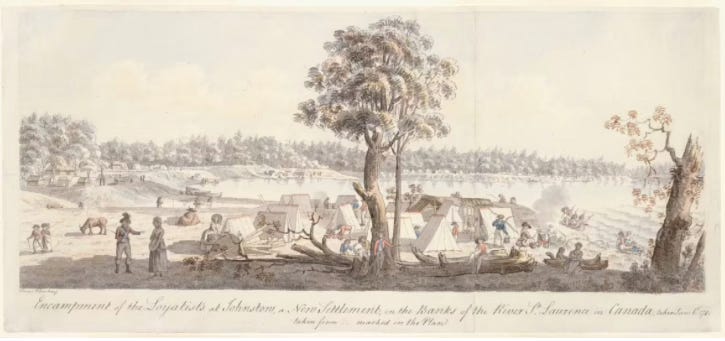

(A sketch of the first encampment of Loyalists in 1784 at New Johnstown on the St. Lawrence, today the town of Cornwall, Ontario.)

Brant, Butler, McDonell, Haudenosaunee and other ‘Tories’ who followed Guy and Sir John Johnson to Canada in 1775-76 came after the peace of 1783 to form a large share of the population upstream of Akwesasne, joining other indigenous communities on the Great Lakes and a large French Canadian farming settlement around Detroit. When Upper Canada was proclaimed in 1791, Brant was its most influential First Nation leader and McDonell the speaker of its new house of assembly.

The American invasion of 1775 was an existential threat to Canada. If Québec had fallen and remained in American hands, Congress might have successfully pressed for sovereignty over the entire Great Lakes watershed. As it was, the successful defence of Québec was primarily due to the loyalty of indigenous warriors, French Canadian militia and re-enlisted Highland Gaels. They had motives rooted in the Covenant Chain, the Great Peace of 1701, the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Sir William Johnson 1764 Treaty of Niagara, the prospect of land grants, the right to hold office and practice as Roman Catholics, as enshrined in the Quebec Act of 1774.

Under Brant, Deserontyon and the Hill brothers, Mohawks and other Haudenosaunee settled in large numbers after 1783 on the Bay of Quinte and the Grand River in what became Upper Canada. Loyalists from the Mohawk valley settled at Sorel and at Montréal; in the Eastern district of Upper Canada and the Niagara peninsula; and at York, later Toronto. Most members of Butler’s Rangers and the King’s Royal Regiment of New York settled in Upper Canada, as did at least sixty veterans of the 84th — many of them in the new county of Glengarry just west of Lower Canada.

Guy Johnson left his home on the Mohawk because the rebels he saw gaining influence at Albany and Philadelphia were, to his mind, violent usurpers. As they called into question his authority as superintendent and overthrew the local structures he and his associates had built, he and Brant understood the only way they could continue in any of these capacities was from Canada.

The decision to leave and to fight was not easy. Guy Johnson died in London in 1788; Thayendanegea passed away in 1807 at his home at the head of Lake Ontario in Burlington, Upper Canada. Many First Nations and loyalist exiles never regained the prosperity they had enjoyed in the Mohawk valley. They stayed loyal to the crown only because of alliances, institutions, laws and treaties that defined them.