One Bar Graph

Canada's Decade of Stagnation

Canadians are fair-minded people. When our leaders make promises, we assume good faith and expect they will do their best to deliver. In 2015, the Liberal Party of Canada platform (‘Real Change’) was entitled ‘A New Plan for a Strong Middle Class.”

It opened with the following words: “A strong economy starts with a strong middle class. Our plan offers real help to Canada’s middle class and all those working hard to join it. When our middle class has more money in their pockets to save, invest, and grow the economy, we all benefit.”

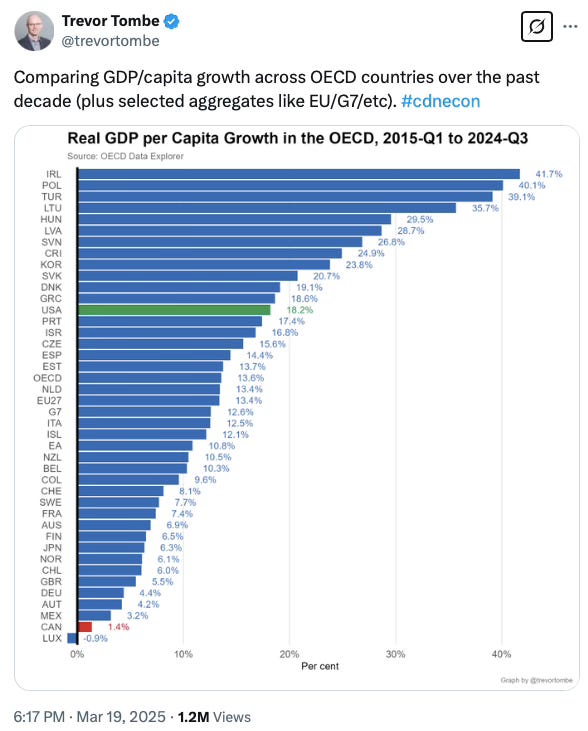

So did Canadians ‘save, invest, and grow the economy’ from 2015 to 2024? The best one-slide assessment is here:

Trevor Tombe, professor of economics at the University of Calgary, has focussed on Canada’s declining per capita income relative the US for a while. This tweet with the bar graph was viewed 1.2 million times.

Outside of the Great Depression, when all leading economies stumbled, Canada’s poor relative performance since 2014 is without precedent.

Even during Pierre Trudeau’s time in office – a period of high inflation and growing deficits – Canada’s per capita income, according to World Bank and OECD data, grew from US$3,473 in 1968 to US$13,477 in 1983. In 2014, it peaked at $51,961.

Income per person has gone downhill, in relative terms, ever since.

Why this setback? I laid out some reasons earlier this month. Books and doctoral dissertations will be written on this subject. Three issues are crucial.

First, over a decade when Moscow invaded Ukraine and allies rightly sanctioned Russian businesses for that aggression, Canada failed to emerge as swing supplier or substitute. We failed to unlock the full potential of our oil, gas and mining sectors – or build large-scale infrastructure needed to reach Europe and Asia.

Outflows of foreign investment from Canada’s oil patch in 2016-17 were particularly brutal. The combined weight of pipeline and tanker bans, slow project approval, federal regulatory burdens and a punitive carbon tax, not faced by US competitors, held the sector’s growth back. Mining also suffered.

Second, Canada went from having a competitive tax framework, which attracted investment, to having one investors saw as uncompetitive and second-rate. Even Canadian pension funds have mostly invested elsewhere.

Third, our federal finances deteriorated. While per capita federal debt in Canada is still among the lowest in the G7, it grew sharply during and after the pandemic.

These trends sound banal: their combined effect has been shattering. Look again at Tombe’s bar graph: since 2014, Canadian per capita income grew, on average, less than that of Britons enduring Brexit; or Hungarians under autocrat Orban; or Germans experiencing the near-collapse of a postwar economic model.

Even Italy and Greece, despite grappling with the aftermath of the 2014-15 migration crisis in the Mediterranean, have done better than Canada.

Only tiny Luxembourg did worse – but their starting point was the highest GDP per capita in Europe, more than double ours.

Far from strengthening the middle class, our last government presided over a decade of income stagnation — triggering cost of living, housing and affordability crises.