One Chart

Canada's business investment rate wilted in 2015

(Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd Meadowbank Complex in Nunavut)

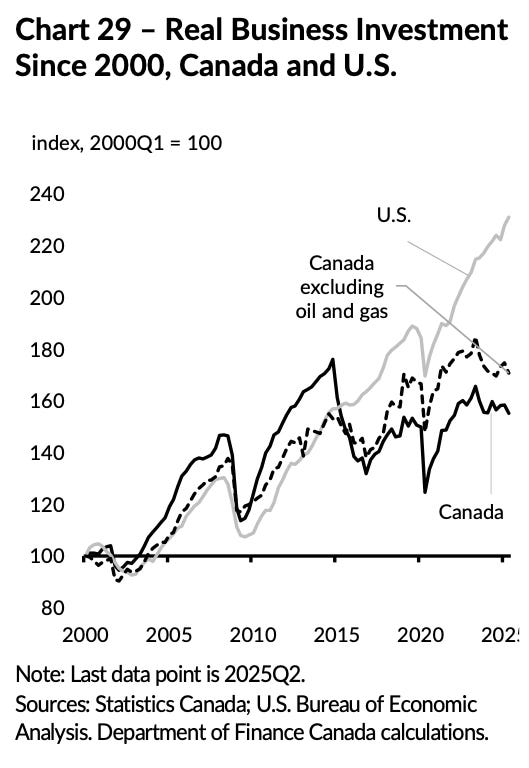

This week’s budget covers many weighty topics. But Canada’s economic predicament is summed up most pithily by a single chart appearing on page 55 of the main document. This graphic is in a chapter entitled ‘Building a Strong and Competitive Economy: Canada’s Path Forward is to Improve Productivity’. Here is chart 29 from the 2025 federal budget, with all its simple candour:

Back on March 28th – exactly one month before our last federal election – our essay on ‘one bar graph’ illustrated how Canada’s per capita GDP had stagnated over a decade. The chart above shows what lies behind that ten-year stall.

Failing business investment is not an abstraction. It has shaved at least $130 billion off our GDP — over $3,000 for every Canadian. It has contributed to declining labour productivity and, by shrinking the tax base, has fed higher federal deficits.

Look closely at the chart above. It shows that from 2003 until 2015 Canadian rates of business investment were higher than in the US, with a short-lived, narrow exception in 2009-10. Since 2015, business investment rates in Canada have fallen far behind the US. Today US investment rates are almost 50 percent higher than in Canada.

Why? First, Canada made itself less competitive. For instance, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in the US reduced corporate rates from 35 to 21 percent, while accelerating machinery and equipment (M&E) and intellectual property (IP) write-offs. Canada’s corporate tax rate has remained at 15 percent since 2012.

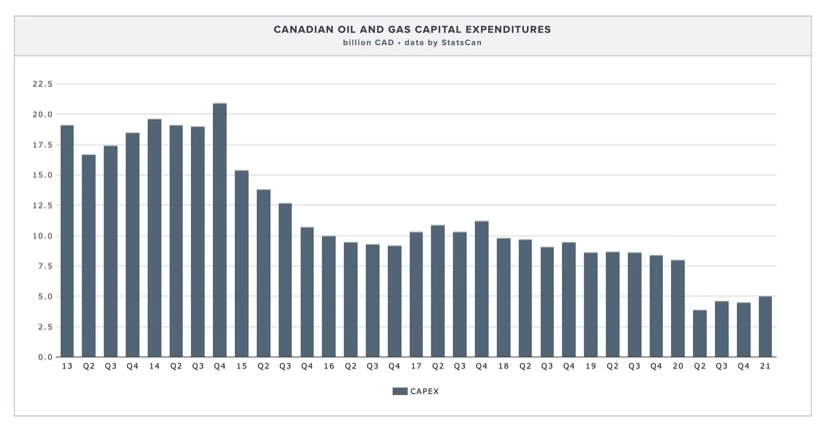

Second, we made it harder to obtain approval for major natural resource projects. We banned tanker traffic, cancelled pipelines, introduced a carbon tax, capped emissions for oil production and dragged out environmental assessments. Mining executives went from rating Canada #5 in the world for permitting certainty in 2015 to rating us #25 in the latest survey. ConocoPhillips, Shell, Chevron, Kinder Morgan, Devon Energy, BP, TotalEnergies, Equinor (formerly Statoil) and others — almost every oil major — either fully exited or drastically reduced their exposure to Canada’s oil sands. This disinvestment covered over $40 billion in total asset sales value. It was a huge vote of non-confidence in our single biggest export sector.

(Capital expenditure in Canadian oil and gas from 2013 to 2021)

Third, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) per worker in Canada began stagnating around 2014. By 2021, real investment per worker had declined by 10-15 percent while it rose in the US. As noted above, investment in natural resources was cut in half. By 2023, overall investment in M & E had also fallen to 41 percent of US levels; for IP, it dropped to 30 percent of US levels. At the same time, an over-heated Canadian real estate combined with a spike in non-resident numbers to price many workers out of their local housing markets.

This was not just poor performance. It was abysmal under-performance, driven by disastrous economic polices. This is not an exaggeration. From 2015 to 2025, every G7 country except Canada saw GFCF per worker increase in US dollar terms. Every Nordic country, the three Baltic states, the three Benelux states, Austria, Switzerland, Poland, Romania, Ireland, Czechia, Spain, Portugal and Korea – all saw GFCF per worker increase over that decade in USD terms.

Of these countries, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Poland, Czechia, Ireland, Korea and the United States saw double-digit increases. Only Canada saw a decline – from US$21,900 in 2015 to $21,500 in 2025, as the Trudeau government took decisions that drove business investment downward for a decade.

At a time when Canada should have been rapidly expanding exports to support allies seeking energy alternatives to Russia, we turned them down by literally cancelling and repelling potential investments. On July 5th, 2016 — two years after Russia’s invasion of Crimea and parts of Donbas — Trudeau told reporters in Montreal: “On the Northern Gateway pipeline, I’ve said many times, the Great Bear Rainforest is no place for a crude oil pipeline.”

On August 22nd, 2022, during a visit to Canada by German Chancellor Scholz, who was scrambling to find alternative sources of LNG after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Trudeau said: “There has never been a strong business case because of the distance from the gas fields, because of the need to transport that gas over long distances before liquefaction.” When Canada refused, other suppliers met the moment.

Trudeau’s decisions were wrong and very costly. Canada weathered the anti-business era of Pierre Trudeau in part because advanced economies depended less on trade and investment to sustain standards of living in the 1970s than they do today. No country has that luxury anymore..

Business investment drives national income and prosperity. Over the past decade, corporate capital expenditures worldwide rose from US$14 trillion to over $18 trillion. Venture capital, private equity, public market and infrastructure capital expenditure grew even faster. Yet Canada saw a decline in capital spending per worker.

We need to remember the bigger picture. The oil sands still managed to increase production. More of this sector is now controlled by Canadian companies. Canadian exports increased — though by less than they could have if proposed major projects had gone ahead. Our economy still has immense potential. But a huge opportunity was lost. It will take a gargantuan effort to restore Canada’s competitive advantage and recapture the rates of business investment we used to take for granted..

The last decade of federal policy on business investment was an unmitigated catastrophe. For decades, Canada’s investment patterns favoured low-productivity sectors like residential construction and services, while underinvesting in high-growth areas like technology and manufacturing — but these trends worsened after 2015 due to policies that drove investment away and undercut export potential.

This decade hurt Canadians and had dire geopolitical consequences for our allies. Carney and his team seem to understand this. They are right to highlight the challenge. Are they doing enough to change course – to close the investment gap with the US and Canada’s other peers? Time will tell. In the meantime, Canadians need to focus on this issue and hold governments to account for their performance.